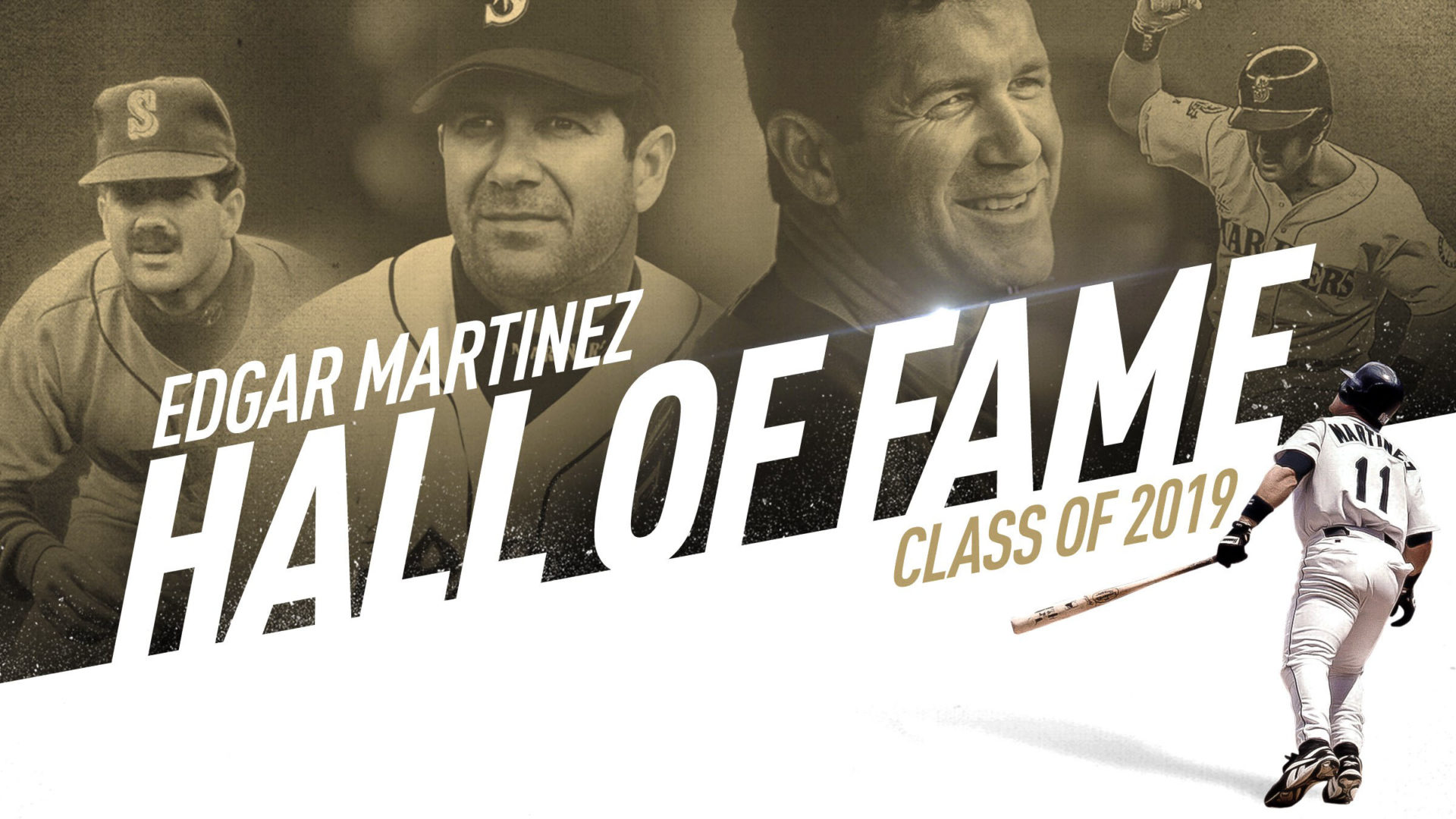

Seattle Mariners hitting machine joins Hall of Fame Sunday

By Dan Trujillo

Eli Sports Network Content Director

(Watch the Hall of Fame Induction Ceremonies live on CBS.com by clicking here)

As teammates for the Seattle Mariners for 11 seasons, Edgar Martinez and Ken Griffey Jr. will be connected in Cooperstown forever when Martinez is inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame Sunday.

“I’m thrilled we’re going to be teammates again in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. It was lonely being the only Seattle guy,” Griffey wrote in his foreword to Edgar: An Autobiography published in 2019.

Although his numbers are below the standards of Hall of Fame voters – he didn’t have 3,000 hits or 500 home runs and spent more than 70 percent of his career as a designated hitter – there is more to Martinez than meets the eye.

For starters, he didn’t become the everyday third baseman for the Mariners until he was 27, which is when most major leaguers are in their prime. Martinez made his big league debut Sept. 12, 1987, as a pinch runner. Ironic for a player who only stole 49 bases in his career.

“Considering my speed, or lack of it, that makes people laugh,” Martinez wrote in his autobiography.

Two days later, Martinez ripped a pitch off the right field wall in the Kingdome for his first major league hit. The ball bounced around the turf and Martinez made it all the way to third base. It was one of just 15 triples he would hit in 8,674 plate appearances during his career.

Despite hitting .363 in the Pacific Coast League in 1988 and .345 in 1989, Martinez bounced between Seattle and Triple-A Calgary five times.

“The Mariners had never fully committed to me,” Martinez wrote. “In 246 at-bats strung out over three seasons, I hit just .268 with two homers.”

Martinez finally got his opportunity to stick in the big leagues when the Mariners traded away third baseman Jim Presley before the start of the 1990 season. Edgar hit .340 during April that year and manager Jim Lefebvre kept writing his name in the lineup. Settling into the No. 2 spot in front of Griffey, Martinez earned his first of two American League batting titles in 1992.

“A lot has been made about how I could (or should) have been playing regularly in the major leagues much earlier,” Martinez wrote. “I probably lost three prime years – age 24, 25 and 26 – when I was a backup and shuttled between Seattle and Calgary.

“Obviously, my cumulative statistics, like the number of hits and home runs, would have been higher, and that might have helped me get to the Hall of Fame sooner,” he continued. “But at the same time, there’s nothing I can do about it now. I have no control over any of that. I choose just to think about how fortunate I was to be given the chance to play and build a career in the major leagues, even if it wasn’t until I was 27.”

Martinez earned an on-base percentage of .418, which is one point higher than Hall of Famer Stan Musial and the 21st best OBP in the history of baseball. Of the 20 players ahead of Martinez, 14 are in the Hall of Fame.

“Getting on base via walks became a big part of my game,” Martinez wrote. “I walked more than 100 times in four different seasons. In four other seasons, I walked more than 90 times.”

Martinez was proud of his “batting eye,” especially because he suffered from strabismus. He was unable to align his eyes when looking at an object.

“Not a good thing when the object is a baseball coming at 95 mph,” Martinez wrote.

Dr. Douglas Nikaitani, the Mariners’ optometrist, gave Martinez a series of eye exercises to do every day.

“After lunch, I’d spend half an hour to 45 minutes on my eye exercises,” Martinez wrote. “And then right before the game, I would do them for another 15 to 20 minutes just to make sure everything was working right.”

Martinez also recalled the things he did as a kid growing up in Puerto Rico and idolizing Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente.

“The pebbles I would hit that were very tiny, hitting rain drops, throwing a ball against a wall, hitting bottle caps with a broomstick – all of it developed my hand-eye coordination,” Martinez wrote.

Injuries also took a toll. Martinez suffered a severe hamstring tear during an exhibition game on a poorly conditioned field in Vancouver, British Columbia, before the 1993 season. On opening day in 1994, Martinez lost sight of a fastball – remember his eye condition – didn’t get out of the way in time and it broke his hand. Dr. Nikaitani had a heart-to-heart with Martinez after that.

“Just duck. I don’t care,” Nikaitani said in Martinez’s autobiography. “You have 0.4 seconds – a 90 mph fastball, 0.4 seconds; high 90s, even less time.”

Martinez became a full-time designated hitter by the start of the 1995 season. Once he settled into the role, it redefined his career. Martinez hit .356 in 1995 for his second batting title and led the league with 52 doubles.

Perspective from this writer

Baseball fans remember “The Double” Martinez hit that scored Joey Cora from third base and Ken Griffey Jr. from first, helped the Mariners beat the New York Yankees in the final game of the 1995 American League Division Series and saved baseball in Seattle. That game doesn’t happen if Martinez didn’t drive in seven runs in a comeback victory the night before.

I was 15-years-old when my dad took me to game four of the series against the Yankees. A total of 57,180 fans filled the Kingdome that day. I had never seen so many people in one place or heard a noise so deafening. It just kept getting louder and louder.

The Mariners fell behind early, 5-0. I had yet to see the Mariners win a game since I attended my first one at the Kingdome in 1990. And down five in this game, I thought I was going to see them get eliminated from the playoffs … until Martinez hit a 3-run home run down the left field line in the third inning.

As I watched that ball Martinez hit from my seat in the upper deck, it seemed to stop in midair as the crowd roared all around me. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The ball stayed fair, landed in the bleachers and the Mariners were back in the game.

Griffey hit a home run in the sixth inning to give the Mariners a 6-5 lead, but the Yankees tied the score at 6-6 in the top of the eighth. That all changed for good when Martinez came up with the bases loaded in the bottom of the eighth and hit a tee shot off the tarp above the center field fence for a grand slam. Once again, I couldn’t believe what I saw. All I wanted Martinez to do in that situation was hit a fly ball into the outfield to score the runner from third on a sacrifice. Even when the ball took off Edgar’s bat like a rocket, I didn’t think it was hit high enough to get over the fence.

“That one’s gone!” my dad shouted.

“No way,” I replied. “No way, no way, no way!”

The Mariners beat the Yankees 11-8 to stay alive and force a game five. As we headed down the spiral walkway from the top of the Kingdome to the streets below, we joined thousands of fans chanting “Edgar” over and over again for at least a half hour. My dad and I still talk about that game today. We’ll remember it for the rest of our lives.

Professional hitter

The seeds for Edgar’s series-clinching hit for the Mariners were planted in his previous at-bat against Yankee pitcher Jack McDowell. Seattle had the winning run on second base in the bottom of the ninth in a 4-4 game, but Martinez struck out on a split-fingered fastball.

“I swung right through it. It was a pitch I should have and I was very upset when I got back to the dugout,” Martinez wrote in his autobiography. “Norm (Charlton) came up to me and said, ‘Stay ready. You’re going to win the game for us.’”

New York took a 6-5 advantage in the top of the 11th. After Cora and Griffey got on base to start the bottom half of the inning, Martinez had a second chance against McDowell. The stage was set for Edgar to deliver the biggest hit in Seattle Mariners history.

“I walked up to the plate with Norm’s words ringing in my ear, ‘You’re going to win the game for us,” Martinez wrote. “It was bedlam, but I felt calm. I took a fastball for a strike, but I didn’t care. I knew he was going to throw the split.

“I saw myself hitting the ball solid. I envisioned the shape and texture of his split-fingered pitch,” Martinez added. “I got the split, just like I knew I would, and I hit a double into the left-field corner that scored both runs. We won the game and won the series. It’s the at-bat that defined my career, but in a weird way, I felt like I had already experienced it. Because in my mind, I had.”

Worth the wait

Ken Griffey Jr. stated in Edgar’s book that Martinez redefined the designated hitter position. When Martinez retired after the 2004 season, Major League Baseball renamed the Outstanding DH Award – which he earned five times during his career – the Edgar Martinez Award.

“He transformed the DH spot from what it used to be, which was an older guy trying to hold on for a couple more years. After Edgar, teams looked for guys who were in their prime to DH,” Griffey said. “When he wasn’t playing in the field, Edgar studied the game. He was one of the most prepared guys in baseball. Because he had to be.

“Edgar’s mindset was four at-bats – five if he was lucky. So his mindset had to be different than ours. We could go out and play defense. He just had those at-bats to make an impact,” Griffey added. “It was impressive to see him do it day in and day out, to be ready for an at-bat after sitting for 30 to 40 minutes. He made a living doing that.”

On Sunday, Edgar Martinez goes into the Hall of Fame with pitchers Mariano Rivera, Mike Mussina, Roy Halladay and Lee Smith, and designated hitter Harold Baines. Although it has taken 10 years from when he first appeared on the ballot in 2010 to gain 75 percent of the votes needed to get to Cooperstown, Martinez wrote in his book that it’s been worth the wait.

“When the phone call came, it was exhilarating, emotional and deeply rewarding. And I realized that in many ways, the long wait to get to the Hall of Fame, which has been so frustrating at times, was actually a blessing,” Martinez wrote. “It I had made it my first year, my kids would have been too young to fully appreciate what it meant. But now they were able to celebrate right along with (my wife) and me, which made the moment even richer.”